Different Types of Infectious Diseases

In the wake of COVID-19, a new global understanding of infectious diseases has arisen. At the very least, the destructive capabilities of disease and its implications are now acutely felt. This view likely won’t change anytime soon, and one outcome of this pandemic could be a larger focus on individual health and medicinal sciences.

COVID-19 is a viral disease, just one of the four main types of infectious diseases. The others include bacterial, fungal, and parasitic—each different in how they spread and how they affect the body.

Let’s break these down individually to understand the types of infectious diseases.

Infectious Diseases vs. Infections

Before going into the four types, there’s a quick separation of terms. Infectious diseases and infections are often used interchangeably. However, there are slight distinctions between the two. An infectious disease, as defined by the Encyclopedia Britannica, is:

“A process caused by an agent, often a type of microorganism, that impairs a person’s health. In many cases, infectious disease can be spread from person to person, either directly (e.g., via skin contact) or indirectly (e.g., via contaminated food or water).”

While an infection is defined as:

“The invasion of and replication in the body by any of various agents—including bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoans, and worms—as well as the reaction of tissues to their presence or to the toxins that they produce.”

By these definitions, when children receive the varicella vaccine—the vaccine used to prevent chickenpox—they’re receiving an infection without producing the infectious disease.

Put simply, all infectious diseases result from an infection, but not all infections cause infectious diseases. Now that that’s in order, what are the types of infectious diseases caused by?

It All Starts With An Infectious Agent: Bacteria, Viruses, Fungi, and Parasites

The four different categories of infectious agents are bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites. When studying these agents, researchers isolate them using certain characteristics:

- Size of the infectious agent

- Biochemical characteristics

- Method of interaction with the human host

- Treatment options

Bacteria

Bacteria are everywhere. They’re on our phone and computer screens, they’re involved in making yogurt and cheeses, and they help us digest our food. While we encounter millions of these cells every day, there are some types of bacteria that are harmful. These are the pathogenic bacteria.

A bacterium cell is a microscopic organism that’s classified as a prokaryote. Prokaryotic cells (as opposed to eukaryotic cells) are cells with a simple internal structure and no nucleus. Though the cell has no nucleus, it does contain DNA within a nucleus-like region called the nucleoid. Because the cell structure is simpler, most bacteria reproduce rapidly—some species reproduce every few minutes.

Their size ranges from 0.2 and 2 micrometers, on average, and they usually fall under one of three distinct shapes:

- Cocci – Round bacteria (ex. Staphylococci – or staph infection)

- Bacilli – Capsule-shaped bacteria (ex. Streptobacillus moniliformis – or rat bite fever)

- Spirilla – Spiral-shaped bacteria (ex. Campylobacter jejuni – a form of food poisoning)

How Bacteria Cause Disease

Bacteria enter the human host in a variety of methods. The pathogen can physically enter through the mouth, eyes, nose, genitalia, and open wounds, and can be transmitted via airborne droplets, bodily fluids, and skin-on-skin contact.

Once bacteria enter the system, they begin to multiply rapidly. In some cases, such as with the bacteria Salmonella typhi (typhoid), the disease is caused when the bacteria die and secrete toxins that are poisonous to humans.

In other cases, the bacteria settle in the lungs, kidney, spine, or brain and attack the tissue. Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which causes tuberculosis, grows in the lungs where it then enters the bloodstream and spreads throughout the body—attacking multiple areas of the body.

Treatment Options for a Bacterial Infection

There are two common treatment options for a bacterial infection:

- Antibiotics – Also known as antibacterials, antibiotics suppress the serious infection by attacking the cell walls of bacteria. Once the cell wall is compromised the bacteria cells can’t survive in the human body.

- Vaccines – Vaccines are a preventative measure that allow the body to create antibodies prior to being infected by the bacteria. These vaccines are weakened versions of the bacteria, allowing healthy immune systems to easily fight them off and become familiar with the disease.

Viruses

Viral infections and bacterial infections are often confused. The main differentiator? Bacteria are living organisms, viruses are not. Instead, viruses are fragments of nucleic acid (think DNA), that are packaged together in a protein. These proteins (viruses) enter through the cell wall of a healthy individual and use the cell’s replication systems (organelles) to reproduce.

Viruses are also a degree smaller than bacteria. While bacteria are the microscopic scale, viruses are on the nanoscopic scale.

Most viruses range between 25 nanometers, such as the poliovirus, all the way up to 250 nanometers, such as the smallpox virus.

How Viruses Cause Disease

Once a virus enters a healthy cell, it is invisible to the antibodies which circulate the bloodstream. Thus, a different mechanism is needed to identify infected cells and eliminate them. This is done with the help of the molecule: class I major histocompatibility complex proteins (MHC class 1).

MHC class 1 proteins encode the contents of the cell’s insides and then present that information externally. Part of the virus’ protein is encoded and can then be detected by T cells.

Once the T cell has identified an infected cell, it releases cytotoxic factors (cytotoxic, meaning toxic to cells) that kill the cell. The invading virus can then no longer use the cell to replicate.

The physical symptoms of a viral infection are when the body is killing off infected cells.

Common Viruses

The seasonal flu is one of the most well-known viruses. And while the flu often sounds innocuous, its numbers are staggering. Between 2010 and 2019, the CDC estimated between 9 million and 45 million infections, as well as 12,000 to 61,000 deaths occur per year, in the US alone.

While vaccines are available each year, the flu mutates so quickly it renders previous vaccines ineffective.

Other common viruses include:

- Common cold

- Norovirus

- Stomach flu

- Hepatitis

Treatment Options for a Viral Infection

Viruses are harder to treat than bacterial infections. This reflects how viruses operate. To kill a virus, the cell where it’s hiding has to be identified and eliminated. But no current medications can do both of these two processes simultaneously. Instead, there are two major treatment options for viruses:

- Antivirals – While antibacterial drugs attack and kill bacteria, antiviral drugs do not attack and kill viruses. Instead, they identify which cell is infected and then contain the virus within the cell, preventing it from reproducing. Because of its “inefficient” methodology, antivirals typically only work when there are few infected cells—it’s recommended that antiviral medications are taken 24 hours from the first sign of disease.

- Vaccines – The vaccines for viral infections work similar to those for bacterial infections. A weakened form of the virus is injected into the body in order to prepare the immune system to detect and fight the virus.

Fungi

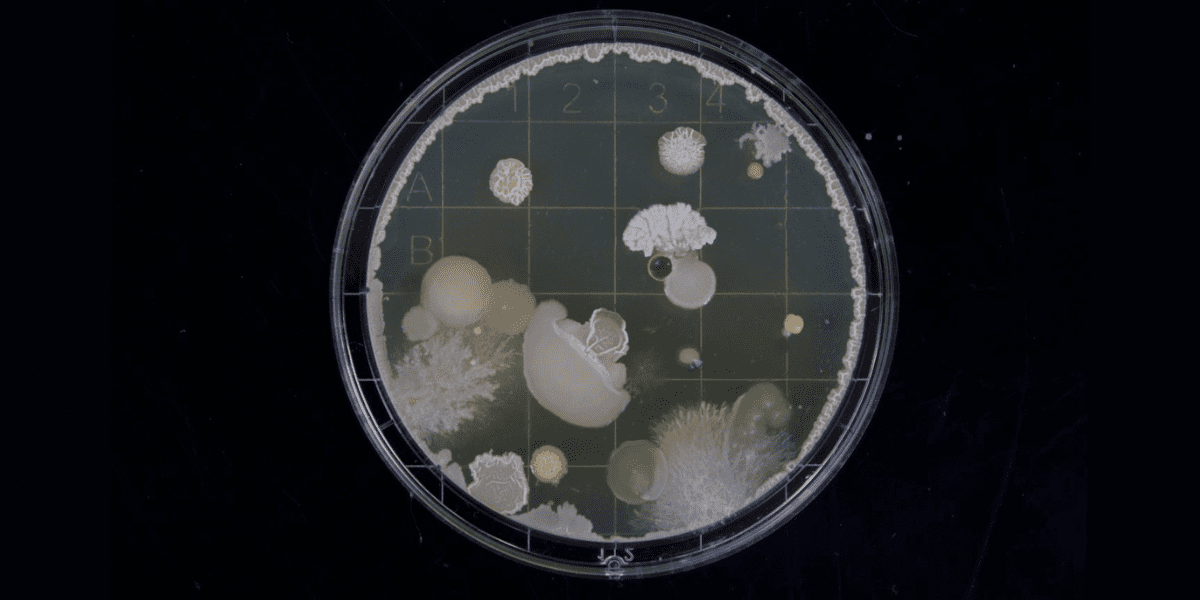

Fungi are typically found on dead or rotten matter (plant and animal) and exist as one of two types of cells: yeast cells or mold cells.

- Yeast fungi – Scientists have discovered 1,500 species of these single-cell fungi. They’re found worldwide on plants, in soil, and in sugary mediums such as fruit. These fungi are the types of yeast that make bread grow and beer and wine alcoholic. Yeast cells range in size from 3 to 5 micrometers.

- Mold fungi – Mold is made up of multicellular filaments called hyphae. These branching structures are between 2 and 10 micrometers and are found on rotting plant and animal matter.

Treatment Options For a Fungal Infection

Certain types of both yeast and mold cells are capable of causing devastating infectious diseases in people. These diseases are called mycoses, common ones being:

- Histoplasmosis

- Coccidioidomycosis

- Blastomycosis

The treatment for an infected person is a combination of antibiotics and antifungals. Antifungals work similarly to antibiotics in that they attack the cell wall, causing cell death.

Parasites

Parasites are living organisms that benefit from attaching to a host, at the detriment of the host itself. Common parasites include everything from malaria, which is about 4 micrometers, to tapeworms that can grow several meters in length.

One can become prone to developing a parasitic infection because parasites will often lay eggs in the host undetected. Only once the eggs hatch is when symptoms of a disease arise.

Treatment Options for a Parasitic Infection

Many treatment options are not approved by the FDA because the demand in the US for antiparasitic drugs is so low. However, the approved drug options include:

- Artesunate

- Diethylcarbamazine (DEC)

- Melarsoprol

- Nifurtimox

- Sodium Stibogluconate (Pentostam)

- Suramin

These drugs attempt to break down the DNA commonly found in parasitic agents.

Studying Infectious Diseases

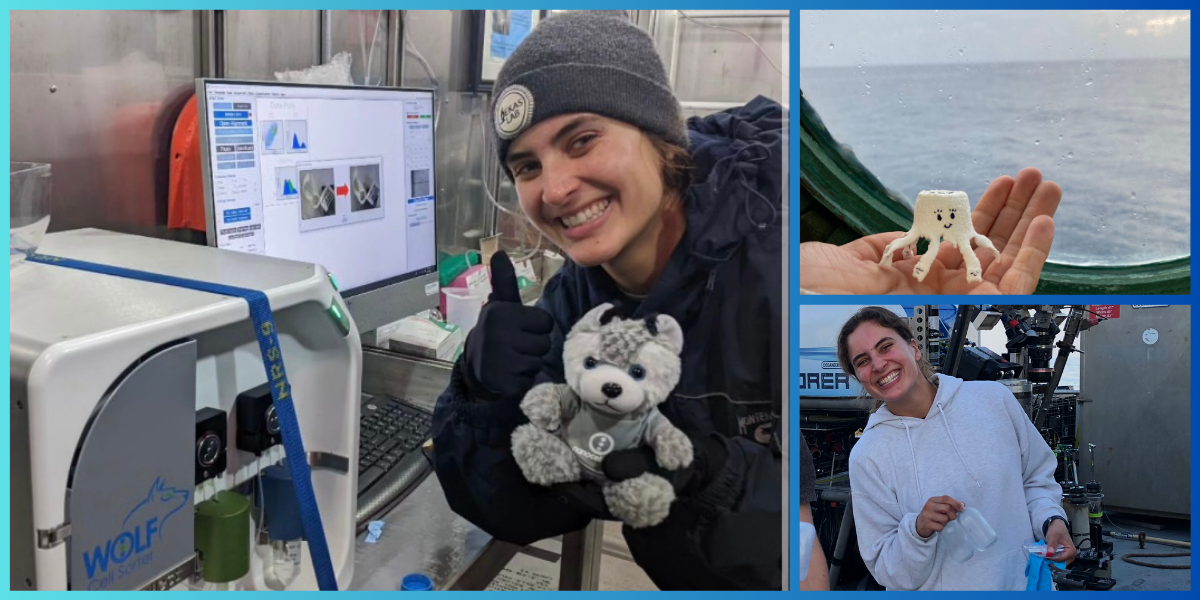

When it comes to studying all these different types of infectious diseases, new technologies have allowed significant advancements to occur. One of these technologies? Flow cytometers.

While flow cytometry has been around for decades, traditional machines have used far too much pressure, damaging the cells in question, causing cell death and obscuring the data.

That’s where NanoCellect’s WOLF G2 Cell Sorter comes in. NanoCellect allows researchers to use modern flow cytometry techniques at pressures of less than 2 psi, gently isolating and sorting infected cells for further study.

It’s compact, intuitive, and it comes with disposable cartridges to avoid cross-contamination between samples.

When is comes to gentle cell sample preparation and single cell genomics —the research starts with NanoCellect

Sources:

- Encyclopedia Britannica. Infectious disease. https://www.britannica.com/science/infectious-disease

- Live Science. What Are Bacteria? https://www.livescience.com/51641-bacteria.html

- LibreTexts. 22.2B: Prokaryotic Reproduction. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Introductory_and_General_Biology/Book%3A_General_Biology_(Boundless)

- MicrobiologyInfo.com. Different Size, Shape and Arrangement of Bacterial Cells. https://microbiologyinfo.com/different-size-shape-and-arrangement-of-bacterial-cells/

- British Society for Immunology. Immune responses to viruses. https://www.immunology.org/public-information/bitesized-immunology/pathogens-and-disease/immune-responses-viruses

- CDC. Disease Burden of Influenza. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html

- Urology of Virginia. How Viruses Work and How to Prevent and Eliminate Them Naturally. https://www.urologyofva.net/articles/category/healthy-living/4126629/how-viruses-work-and-how-to-prevent-and-eliminate-them-naturally

- Encyclopedia Britannica. Yeast. https://www.britannica.com/science/yeast-fungus

- CDC. Parasites – Health Professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/health_professionals.html