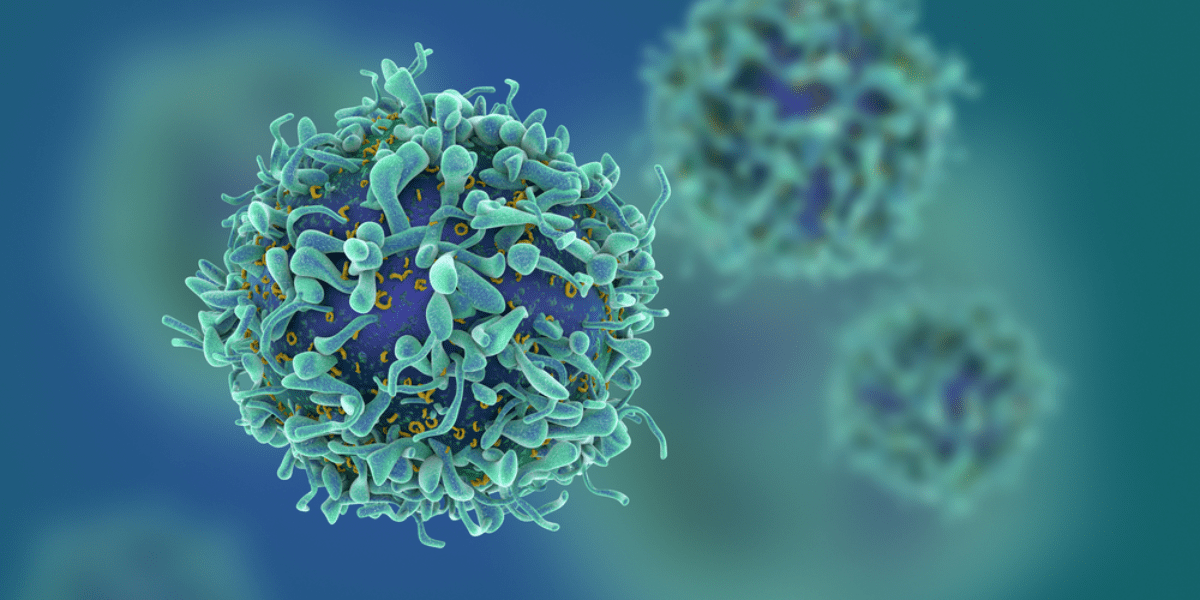

Flow cytometry is a useful technique used in cell biology, cancer testing and research, stem cell research, and many other fields. Using a flow cytometer is a method of measuring—organizing, in as sense—microscopic cells found in a heterogeneous solution.

If you’re reading up on this topic as a refresher, welcome. If you’re new to flow cytometry, don’t worry; this guide is here to break down flow cytometry and the basic principles behind its utility.

Already know the basics of flow cytometry? Skip ahead to Applications of Flow Cytometry.

If you’re new, put on your goggles, strap on your fluorescence gear, and prepare to get excited. If you didn’t laugh at this pun, you will soon.

In its essence, “Flow” refers to fluid or motion. “Cyto-” is a prefix, often used in biology that relates to “cell” or “cells” and “-Metry” relates to “measure” or the “process of measuring.”

Thus, putting it all together:

Flow cytometry uses three basic scientific principles—fluid dynamics, optics, and electronics—to detect, count, and do cell sorting. This process solves two primary pain points:

Because of these, flow cytometry is incredibly useful for measuring and analyzing the cells one at a time. How does it accomplish this?

The first step in flow cytometry is taking a flow cytometry test – taking a heterogeneous sample and injecting it into the sheath fluid.

Because of hydrodynamic focusing, when the heterogeneous sample is injected into the sheath fluid (at a slightly higher pressure), the cells migrate into a single-file line to be passed through a laser beam.

Aha! So this is where optics comes in, huh? Right you are.

With flow cytometers, thousands of cells can be analyzed and sorted per second. But what allows for these precise measurements at such a high speed? The first part comes from laser optics.

When the cells stream past the laser one at a time, their cell structure refracts part of the beam. Some of the light refracts past the cell to a detector behind, while other detectors sit at a 90-degree angle to measure the side refracted light.

Clearly this won’t identify which of the five white blood cells are currently running through the laser. However, it does help differentiate them partly. To identify fully, FSC results must be combined with SSC.

Combining these two detection methods allows for a great deal of differentiation between cells.

A question that has yet to be answered is how the laser “targets” each cell one at a time, despite being within a sheath fluid.

Remember the hilarious pun you read earlier? Okay… the hilarious pun that you didn’t laugh at? Well, this has to do with how the heterogeneous fluid is “labeled.”

When oncologists want to measure and detect cancer cells in a patient’s body, a typical practice is for the patient to ingest radioactive iodine or another form of a radionuclide. The tissues surrounding the cancer (and some of the cancer cells themselves) will absorb the radioactive material and light up on the appropriate scan (PET scan, bone scan, etc.).

Either way, this allows oncologists to point directly to cancer and measure its severity in a patient.

How does this relate back to flow cytometry? Great question.

Flow cytometry uses a similar principle. By utilizing a proper fluorescent label, otherwise known as a fluorochrome or fluorophore, you can target certain cells within a heterogeneous solution, or even target specific proteins within a cell itself. This can be achieved with fluorescently dyed and labeled antibodies that are highly specific that attach to normal cells or proteins. When the laser light hits the desired cell, the fluorescently dyed antibody gets excited and emits photons (causing the FSC and SSC to be detected).

To quickly recap, the cells to be measured are injected into a shear fluid at laminar flow. This creates the single-file march of cells toward the laser. The laser excites the fluorescently dyed cells, which create both forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC). Scattered light funnels through filters and mirrors to reflect into photo-multiplying tubes, detectors that are calibrated to detect a certain wavelength.

From here, the third and final principle applies: electronics.

Each PMT detector converts the fluorescence signal into a digital, trackable data point. These data points then create impressionistic images that can be analyzed to measure the different cells apparent in the heterogeneous fluid.

The ability to measure multiple cell characteristics at one time with an automated process is invaluable to many different fields. And the most common applications include:

One of the largest pain points when operating flow cytometers is keeping the cells alive throughout the process. Because of apoptosis, cells that die within the cell sorter are not only useless for the secondary measurements and tests, but they create noise within the data.

Cells die from being over-oxygenated, under significant pressure, and of course, they die randomly as well.

In order to limit this pain, NanoCellect created the WOLF Cell Sorter. With a sorting pressure that is 30 times gentler than standard sorters (less than 2 psi), the WOLF Cell Sorter is able to help biopharmaceutical companies, labs, and more keep their cells alive when isolating.

In sum, to sort and analyze cells, it has to be done one cell at a time. Doing this manually is out of the question, and flow cytometers rely on basic principles to automate this process. Fluid dynamics and hydrodynamic focusing allows cells to stream past a laser one at a time. The principles behind optics allow the scattered light to be detected. And finally, electronic systems record the flow cytometry data to be analyzed further.

For a cell sorter that utilizes these principles and optimizes their effects to keep cells happy and healthy, think WOLF Cell Sorter.

Think NanoCellect.